In Search of a New Commons

Why communal relations & enclosure in medieval England still matter, plus a recipe for the garlic mustard that's trying to take over your yard

I return to this idea of “the commons” over and over again. I sense it unfurling underneath my daily life - something that once was a regular feature for my Anglo-Scots-Irish ancestors fossilized in my body, holding a shape that now is remarkable only because it’s filled by empty space.

It was only a few hundred years ago but it feels fully mythic to me, the slow slide from communal relations into individualized, atomized social relations and near-total alienation from the land we live on. But I need to remember not to romanticize too much - the commons were not a paradise, even though it’d be tempting to cast them in that light from this vantage.

No, “paradise” is not one of the words that could be used to describe rural village life in the British Isles before the 1500s. But people worked and lived in very different ways that are compelling to me. Before the potato famine came to Ireland, before wage labor and factories and the depopulation of the countryside, people made their livings in a variety of ways but the wild and wooded areas were considered common property to all. Anyone could hunt or fish or forage there to support themselves and their family.1

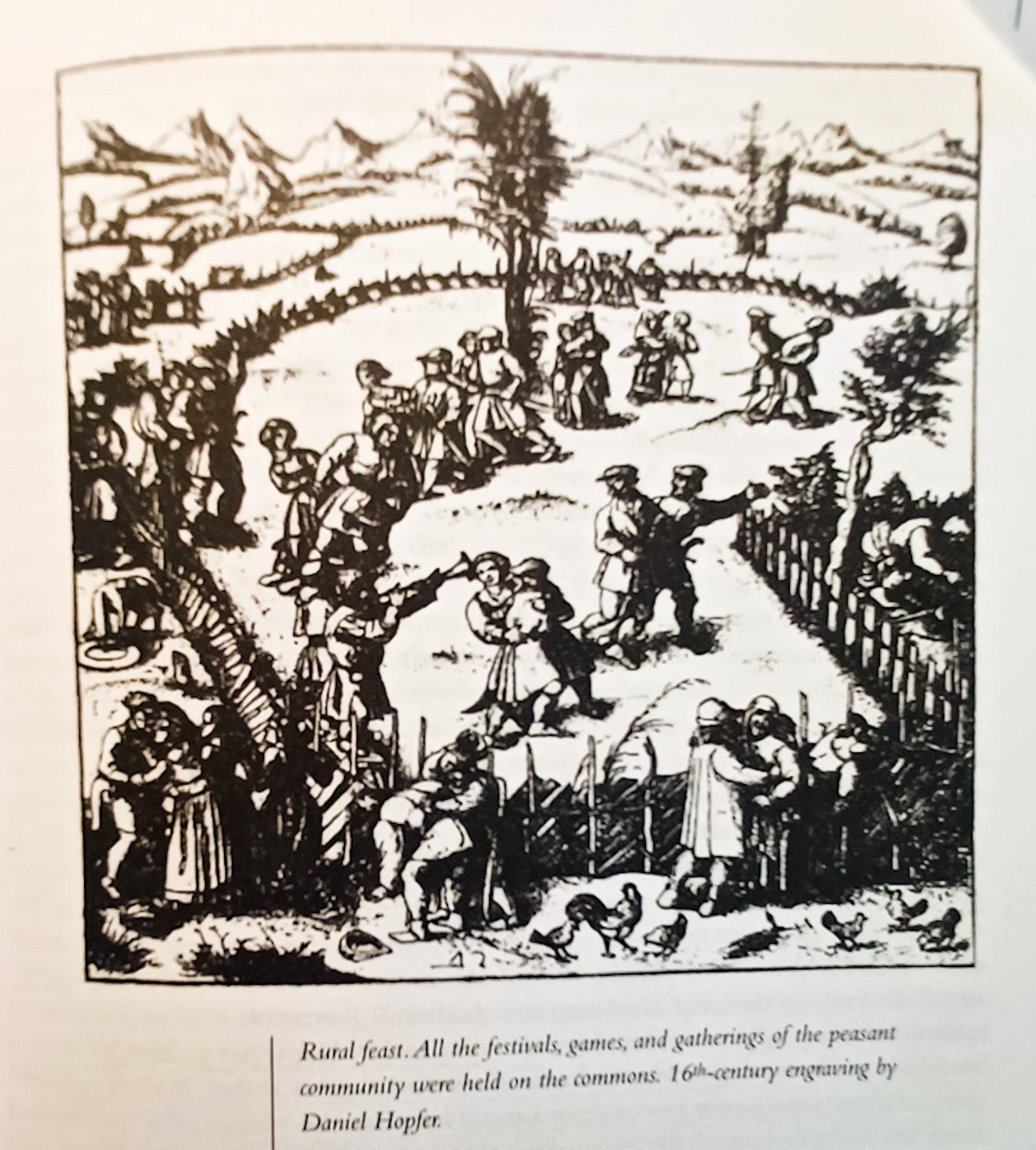

This is important because it gave community members bargaining power with the local lord, in whose service they were often pressed for things like annual haying and taxes. When you know you can live off the land you are never desperate for work, you are never forced to accept unacceptable terms. The existence of the commons also kept the very poor from starving, and it was a place where people came together for festivals and games. Solidarity and cooperation are the social relations that the commons breeds, though surely imperfectly - decisions about the commons were often made democratically by peasants’ assemblies.

In the 1500 and 1600s the process of enclosure began, in which wealthy landowners and the British government began clearing and literally fencing off the commons so that sheep could graze and farmland could be consolidated in the places that had once supported people in addition to innumerable other species. This took place in the name of modernization and efficiency. In its wake, agriculture did become more productive, but for exporting product abroad, not for feeding the people who actually lived nearby. You may recall that wool was a huge export from the British Isles around this time, and enclosure made that industry possible. It also deprived people of their ability to sustain themselves, which forced them to move into the cities to work as wage laborers in factories, effectively ending the rural way of life for many.2

The enclosures were fought against bitterly by the peasantry, who uprooted and destroyed the hedges that enclosed the land that had helped to support whole communities. One of the most notable uprisings was Kett's Rebellion in 1549, in which some 16,000 rebels took the city of Norwich and held it for nearly a month against the Royal Army.

The thing about enclosure is that it didn’t end with the textile industry in the UK – it is still happening all around us. No Trespassing signs on swaths of land where walkers have rambled for eons. The continued encroachment of work into your free time through the constant access to cell phone and email, the gig economy, remote work, productivity hacks, the cult of always, always be optimizing your body and mind and time.3

I think this is one of the reasons why foraging has become so popular in the last few years - there is something missing that is felt deep in our bodies. I remember the grief I felt when I learned about the enclosures and the end of the commons as a lifeway (that I still feel!). “Connection” is the easiest word for what we’re missing - a way of being involved in the landscape, being a participant instead of a watcher. But it’s also the reason that home gardening - while I feel very lucky to have space to grow some of my own food - is always ultimately a little unsatisfying. There should be a place for all of us to find sustenance in many forms and to collectively do the work of tending.

Euell Gibbons, author of the excellent wild food guide Stalking the Wild Asparagus, believed that the more people who were actively foraging, the more wild lands would be preserved. Unfortunately, this does not seem to be the case in the United States. The U.S. Forest Service estimates that “[t]he United States loses about 2 million acres of forest, farm, and open space each year” to development.4

Maybe one place we can see the commons emerging - in its own specific context - is the Weelaunee Forest, also known as the Atlanta Forest, which folks there have been fighting to defend and preserve over the last two+ years while the local police force attempts to build an enormous training facility there. Many, many different organizations and people have come together to bring the community en masse into the Weelaunee Forest and not only exhibit its natural abundance, but also to organically create social dynamics that would not exist outside of this site of resistance.5

If you have followed this issue at all you have seen that the retaliation from the police and the city government has been extreme, including the murder of one forest defender and domestic terrorism charges for people grabbed at random while attending a music festival being hosted in the forest (a public park). Perhaps in this example we can see how the commons is always a threat to the powers that be - the mere fact of its existence displays another path, another set of possibilities and potentials, other ways of being in the world.

And so we should not despair, there is too much to be done. There’s no one answer, there’s no one way through - context is always critical and incredibly specific. Getting involved in your local conservation groups, learning how the indigenous people who lived and still live in your area have planted and managed the ecosystem, learning to identify the native plants and the non-native ones, learn how your own ancestors tended and prepared their foods. Tomorrow I’m joining the Champaign County Forest Preserves to pull garlic mustard from one of our parks. Make it part of your life, let it be joyful, and don’t keep it a secret.

One (okay, really two) Unsolicited Recommendations

I read an excellent essay about the shortcomings of the “Eat the Invasives” mantra (tl;dr: it doesn’t really work on the scale that it needs to in order to be effective under capitalism; i.e., if it can’t be profitable for someone) by Nicholas Gill which you can read right here.

I love reading things that make my stances more complex and nuanced (in this case, as an enthusiastic proponent of eating invasive species), *and* it’s still garlic mustard season motherfuckers!!! One of my favorite invasive species to eat. So here’s a recipe for you. You need:

A block of soft tofu

A big handful of garlic mustard leaves

Squirt of lemon juice

A few tablespoons of nutritional yeast

Salt & pepper to taste

Throw all of these things into the food processor and blend until creamy. Taste, adding whatever ingredients you want until you are ready to devour the entire thing. I like to schmear on toast or scoop with salty crackers.

Comment if you’ve got another favorite way to enjoy garlic mustard! Happy eating.

Thanks for being here and see ya next time,

Mere

This legacy of customary rights still exists in some ways in some places - the customary right of gleaning can be seen in Agnes Varda’s incredible documentary The Gleaners and I.

These are complicated issues with complicated histories – obviously my renderings are in broad strokes for the sake of brevity. For a ton of information about the process of the enclosure of the commons, the primitive accumulation of capital, and how gender is inextricably wrapped up in those processes (especially through the mass witch hunts of Western Europe), please read Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body, and Primitive Accumulation by Silvia Federici. Not a single day goes by that I don’t think about this book.

For a great analysis of the effect of colonization on lands held in common in North America, please see Commons and Enclosure in the Colonization of North America by Allan Greer (it’s JSTOR so you can sign in through your library or sign up for a free account to read). There are some common misconceptions about communal land ownership before the colonization by white settlers that tend to oversimplify a lot of the complexity that existed. One choice excerpt: “We can, then, speak of an “indigenous commons,” recognizing the wide variety of arrangements by which terrain and resources belonged to specific human collectivities in the real America where Europeans came to establish their colonies. Apart from cultivated areas, America was a quilt of native commons, each governed by the land-use rules of a specific human society. The notion of a universal commons completely open to all - Locke’s “America” - existed mainly in the imperial imagination.” (page 372)

Full report can be found here: https://www.fs.usda.gov/research/treesearch/42756

If any of this is new to you you can find a ton of information about the movement’s past and present through the Defend the Atlanta Forest website.