Megan and I have gone beyond the curve of the river, we are very much off the beaten path, we are following the river’s nearly empty bed downstream, the trickles of water rippling shallow over pebbles and stones, relentlessly toward smoothing, mirroring the tree branches and sky back in scraps and fragments. It is hot and thickly humid, past the high point of summer but before we can feel the whispers of the coming autumn. Much is revealed with the river’s lack - what usually is underwater is out in the plain of day for our examination.

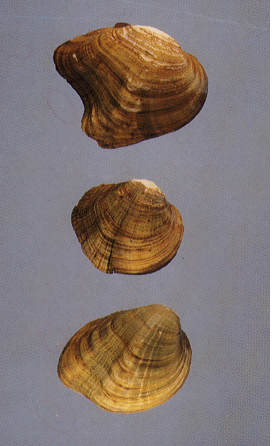

What we are finding are empty shells. Dozens and dozens of them - elliptical mussel shells in all different shapes and sizes. Some are smaller than my pinkie nail and completely white, others are longer than our heads with iridescent purple insides shining in the summer sun. I remember reading an “interpretive plaque” at another nearby park that these shells were used by white settlers for the button-making industry in the old days. Looking at these vacated houses you can see why someone would want to capture this kind of shine.

Of course, freshwater mussels like these are facing annihilation, but we’ll get to that.

Freshwater mussels are perhaps the liver in our waterways - cleaning and removing impurities from the water as they feed - several gallons of water per mussel a day. Half-buried in the river or creek bottoms where the water flows over them continuously, they sip water into their shells in order to feed on what floats therein - algae, bacteria, the teeny guys. “As filter feeders they help clarify water and concentrate impurities in their shells and soft tissues” says Robert Warren of the Illinois State Museum.

Basically, they are the bellweathers that can tell us about the general health of a waterway - the fewer the mussels the more fucked-up the ecosystem - and their mass die-offs are harbingers of the wider ecological destruction to come. And the more I learned about these quiet, nervous system-less creatures the more fascinated with them I became.

The life cycle of the freshwater mussel feels like something that could have been straight out of a myth about how a constellation or a demi-godly hero was born. “Freshwater mussels have an elaborate reproductive system” is how the Illinois Department of Natural Resources puts it. Once baby mussels are formed inside their mother, they are squirted from her body and attach to a “host” fish’s gills or tail to incubate, and to metamorphose. The mother mussel has a part of her body that she will dangle outside her shell that lures in potential host fish because it looks like a little minnow, bait.

The baby mussels grow all their necessary parts while secretly held in the folds of their host fish: shell, pseudocardinal teeth, gills, mantle, foot, and labial palps (let’s read that one one more time: labial. palps.). A mythic trope: children abandoned by well-meaning mothers to be raised in the wild by another species. When they are ready, they drop off the temporary vessel of the swimming fish and bury themselves where they land, to inhale the water and exhale it cleaner than it was, a labyrinth of soft tender folds inside, hard protective shell on the outside. Some of them can live like this for up to one hundred years.

Freshwater mussels have been decimated throughout the eastern United States and may be the most endangered group of animals in North America (Williams et al. 1993). “Of the approximately 300 species of freshwater mussels found in North America, 70 percent are endangered, threatened, or in need of conservation. In Illinois, 21 mussel species are listed as endangered and three as threatened.” Siltation, an increase in silt in their habitats, is the biggest danger, it literally smothers them as they lie submerged in the river or creekbed.

Siltation is one result of the way that industrial farming is done in the US. After the herbicide and fertilizer-soaked monocrops of corn or soybeans are harvested in the fall, the bare ground sits vacant all winter, topsoil eroding unabated into the nearby waterways. This is not only disastrous for the long-term soil health (and the literal ability for the land to produce anything), it is devastating to the downstream ecosystems (you may already be aware of the dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico, a direct result of this erosion, which reached around 8,000 square miles in 2019). These killer nutrients are carried by the eroded topsoil particles, which pile up in the riverbeds and wipe out whole populations of freshwater mussels, who again, are the upstream bellweathers of looming catastrophe.

However, in this area there are some positive changes that seem to be percolating. The rise in “regenerative agriculture” is making a difference - the USDA has made new funding available to farmers so that they can plant cover crops over the winter, which keeps the topsoil in place instead of letting it erode. I’ve been happy to see a few fields out in my neck of the woods in rural central Illinois planted over this year’s winter, much more than last year but still far from the majority. Hopefully the program will be successful and more and more farmers will be able to participate. The Farm Bill could be useful in making these big changes but it seems that the deeply entrenched political divide will keep anything meaningful from happening. The upshot is, as always, that we need to re-imagine the way that farming happens on a systemic level in a way that works for farmers, the public, and the planet.

How much do you know about your watershed? In this part of Illinois we’re lucky to have organizations like Prairie Rivers Network and even more specifically the Upper Sangamon River Conservancy. Who’s looking out for our mollusk friends (and all our other friends who depend on the river of every size - including humans) in your neck of the woods? Are there ways that you can support that work, whether it’s doing a volunteer river clean-up day or donating a few bucks or re-posting their info on social media?

This work feels more urgent to me the more I have learned about the diversity that exists in just this one kind of creature and how greatly diminished it has been over the last century - how we may never know the extent of the losses. So I thought this time I could end with a list of the common names of the freshwater mussels - just here in Illinois - that have gone extinct or are extirpated (they no longer exist in the state of Illinois), and the names of those that we can still save, especially those of “greatest concern.” These species are more precious that any cultured pearl. And if you know someone who has named a freshwater mussel in Illinois, please shake their hand for me, I love these names so much. Let’s imagine what it would look like for all of these species to be thriving in our waterways, and what would have to change.

Extinct or Extirpated (here’s the full list):

Leafshell White Catspaw Combshell Tennessee Riffleshell Wabash Riffleshell Tubercled Blossom Longsolid Cracking Pearlymussel Ring Pink Round Hickorynut Rayed Bean White Wartyback Rough Pigtoe Winged Mapleleaf

Mussels “in greatest conservation need,” and those endangered federally and state-wide

Elktoe Slippershell Rock Pocketbook Rainbow Purple Wartyback Fanshell Butterfly Elephantear Northern Riffleshell Snuffbox Spike Pink Mucket Wavyrayed Lampmussel Higgin’s Eye Louisiana Fatmucket Pocketbook Creek Heelsplitter Flutedshell Little Spectaclecase Scaleshell Black Sandshell Orangefoot Pimpleback Sheepnose Clubshell Ohio Pigtoe Fat Pocketbook Bleufer Kidneyshell Ebonyshell Salamander Mussel Rabbitsfoot Purple Lilliput Gulf Maplelead Pistolgrip Ellipse

Thanks for reading & see ya next time.