We have been hiking in the canyon for days. We have been crossing the serpentine river again and again for days, stabbing our walking sticks into the rocky river bottom to steady ourselves against the thigh-deep rushing onslaught. “The sooner you accept that your feet will be wet the entire time the happier you will be,” my friend, our guide, says at the beginning of the hike. We have been following the stone cairns, we have been watched by the hoodoos and the tarantulas, the moisture slowly leaving our bodies in the faintly red desert landscape, for days. And then there is a bend in the canyon, in the river held by the canyon, and the bone-white limbs of a sycamore tree abruptly pull the breath from my body as they come into view.

In the Gila Wilderness in southwestern New Mexico, these water-loving trees make their stark contributions to the landscape. Coming upon this tree in this terrain so unfamiliar to me, the tree found growing into the banks of rivers all over North America, its roots weaving latticework shells that remain even when the ground erodes away, felt like a revelation, felt like we had arrived somewhere otherwise unreachable.

Perhaps it’s the skeletal suggestion of the sycamore’s branches, as bleached white as a javelina’s remains, the lends the tree its uncanny aspect. The tree that embodies the visual evocation of death while growing, living, thriving. I have found that the sense of hauntedness grows with the size of the trees, who become ghostly giants hanging over a slow-moving river, or anywhere that water is readily available. That’s why I wasn’t at all surprised to learn that the sycamore is the tree found at the gates of the ancient Egyptian underworld.

The American sycamore gets its ghostly form from its unique genetics, its unique expression of tree-ness: as it grows, its bark begins to shed, a process that increases as the tree grows until the top (often the top half and all of the branches) is entirely white, all of its bark sloughed off, like a snake shedding its skin halfway if snakes were trees. It is the queen of the floodplain, the bottomland - often growing from sapling as a “pioneer” species up to over one hundred feet tall, three people with their arms outstretched or more around. And they can live for hundreds of years - five or six hundred not being uncommon.

The large hollows that form in the trunk of the sycamore as they age are another of its distinctive features. If you were like me, a child who loved to run through the woods all day every day and to devour YA wilderness survival fiction (Hatchet and My Side of the Mountain being a couple of the most famous examples), you instantly recognize these hollows as potential places to hide out, to take shelter, to curl up like the soft hairless animal you are. Allegedly, a settler named Joseph Hampton lived for the better part of a year in a sycamore hollow with his two sons in 1744 in the Shenandoah Valley - not a terrible place to hole up for a while in a pinch.

If you have a sycamore or sycamores that you’re acquainted with, you might notice that it’s usually the last deciduous tree to leaf out in the spring. Rather than being just a sleepyhead, a lazybones, the sycamore is usually fighting off a common fungal infection called anthracnose every spring. The sycamore is triumphant most of the time, but the fungus leaves its mark in the form of cankers: areas of dead tree tissue that can create strange shapes, waving bumps under the bark. It also can result in a condition known, delightfully, as witch’s broom, in which masses of new shoots all grow from the same point. These features are easy to spot once you know about them.

“In Egypt heaven is a wetland,” writes archaeologist and poet Susan Brind Morrow in her incredible book The Dawning Moon of the Mind: Unlocking the Pyramid Texts. In a place where water, the Nile, was so clearly the source of life, this makes perfect sense. In the ancient myths, the sycamore was the Tree of Life itself. It was associated with Hathor, the goddess who helped souls transition to the afterlife and was revered for her aspects of protection and fertility. As with everything in the ancient Egyptian texts, the embodiment of a particular aspect of divinity is found in a literal place in the night sky. Hathor is the dappled cow in the Milky Way, she is a specific location in the sky. In the Egyptian Book of the Dead, the dead can lie down to rest underneath the sycamore tree after their long journey to the land of the dead.

To my dismay I learned, after further investigation, that the sycamore in the Egyptian conception of the underworld is not at all the North American sycamore that I have come to know. Not even close, in fact. The Egyptian sycamore is the sycamore fig, Ficus sycomorus, which produces a sweet fruit with a milky sap. My (”my”) sycamore is the Planatus occidentalis (Platanus wrightii in the Gila Wilderness), whose native range is only in North America. In the branching tree of species identification, Ficus sycomorus and Platanus are both eudicots but that’s where the similarity ends. So much for my neat little theory!

But I think about Sophie Strand’s work about grounding one’s cosmology in the ecology of the place where you actually are - and the ways that our religions lose much of the embodied texture of their meaning when we remove them from their ecological context (she wrote a book about this that is excellent). I hunted for information about the place of the sycamore in any American Indian mythology but just turned up some sketchy blog posts repeating the same story about misfortune befalling white settlers who cut down two sycamore trees believed by the local tribe to contain evil spirits.

I am sure that there are stories of the sycamore that have been passed down in ways that are not accessible to me, a descendant of white settlers. I do not need to know them but I do hope that they have not been lost to the world.

I want to be in the practice of seeing my conception of the Divine grounded in the landscape around me. In this way, the whole world becomes holy. The fields of goldenrod are holy. The ripening wild apples are holy. The thirteen-striped ground squirrel, which my friend calls a “squinny,” is holy. The feathered edges of the bur oak acorn, the bright sulfur flush of chicken of the woods mushroom, the beavers trying to dam the Sangamon - holy, holy, holy. I feel the tender prickle of being seen, of being knitted deeply into the knowing fabric of existence, every time the breeze blows through the branches of the trees.

I imagine myself after death, my body abandoned by its life force. The bright snake of starlight found in my spinal column takes its place in the wooden boat at the banks of the river whose name means “place where there is plenty to eat,” the land of milk and honey. The coyotes, the red-tailed hawks, the geese, the monarch butterflies, the spreading fingers of mycelia underground, the squinnies, the Big Dipper constellation, the white-tailed deer, the beavers, the freshwater mussels in their pearlescent shells witness the going-forth: the boat glides without obstacles down the river between two ancient, resplendent sycamore trees and into the mist, returning to that from which I was never truly separate.

What I’m Working On

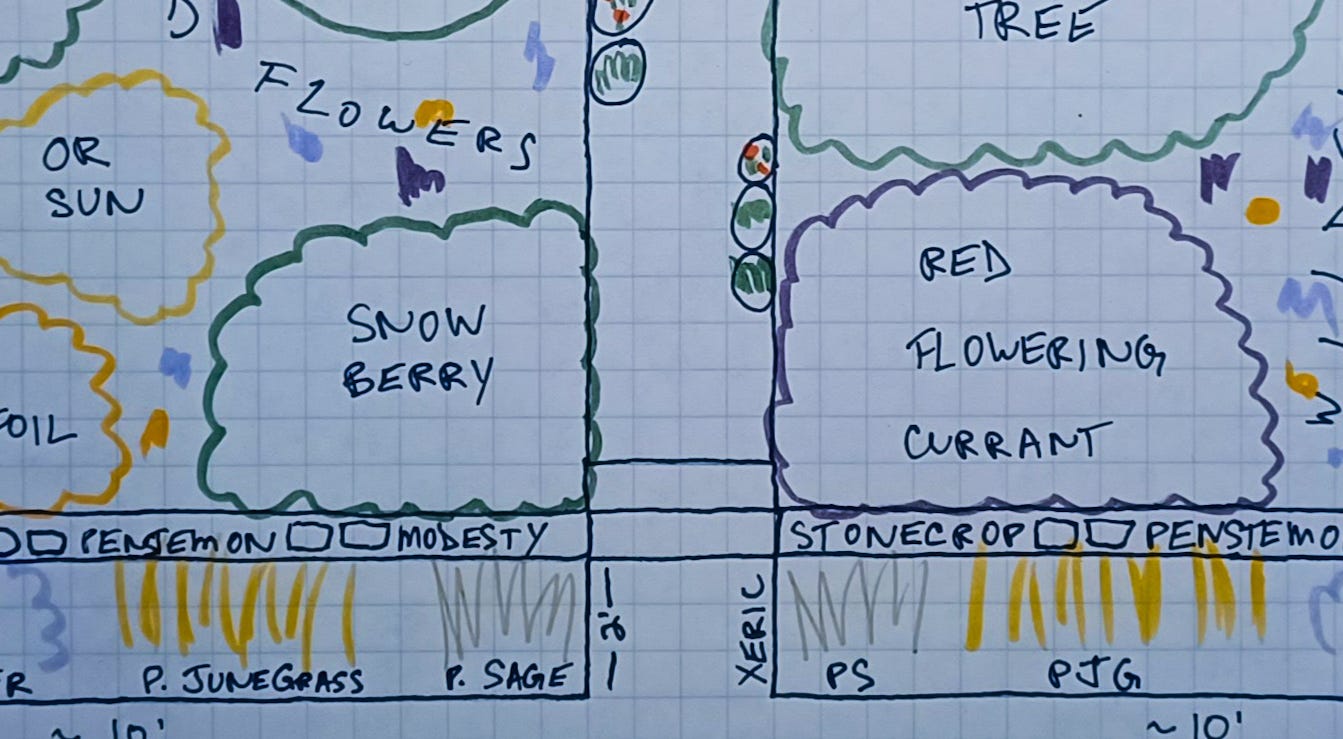

Just finished the yard I mentioned last time - a truly enjoyable jigsaw puzzle of some xeric conditions, the wildly oscillating weather seasons of Portland, Oregon, and the desire to use entirely native plants that provide food and forage for birds, pollinators, and all the bug friends with as few required “inputs” (e.g., compost) as possible.

Next up: another Portland yard that’s seen a ton of improvements since the new owners bought it last year (New fence! Raised beds! Vole removal!), that just needs some more native plants that will thrive in the variable conditions to give that lush, jungly wild yard feeling. I’m so stoked to get started on it.

If you’re interested in hiring me to design an ecological yard or garden for you, wherever you are in the U.S., please just respond to this email and tell me a little bit about what you’re looking for! We can see if it’s a good fit.

As always, thanks for being here.

Holy, holy, holy indeed. So gorgeous.